Ahead of the Q&B Spring Conference, Quaker historian Andy Fincham explores how Quakers grew to prominence in trade, challenging some assumptions about why Quakers were so successful.

It may come as a surprise to discover that the history of Quakerism is just as vulnerable to mythology as any other history. Surprising, perhaps, because our testimony towards Truth might be thought sufficient to ensure that claims made about how our Society developed are both accurate and valid. But we as Quakers are required to challenge ourselves: the evergreen Advice (no.17) which asks us to “Think it possible that you may be mistaken” should apply as much to our history as to our faith in practice.

It remains a curiosity how a Society with relatively few members managed to have such a disproportionate influence. Even at its peak (about the turn of the seventeenth century) it is likely there were fewer than fifty thousand Quakers in England and Wales, and yet they grew to prominence in most spheres of trade in which they engaged, and went on to use their influence to help make positive changes in the wider society – from major contributions in the anti-slavery and peace campaigns, to social justice across prisons, employment and access to education.

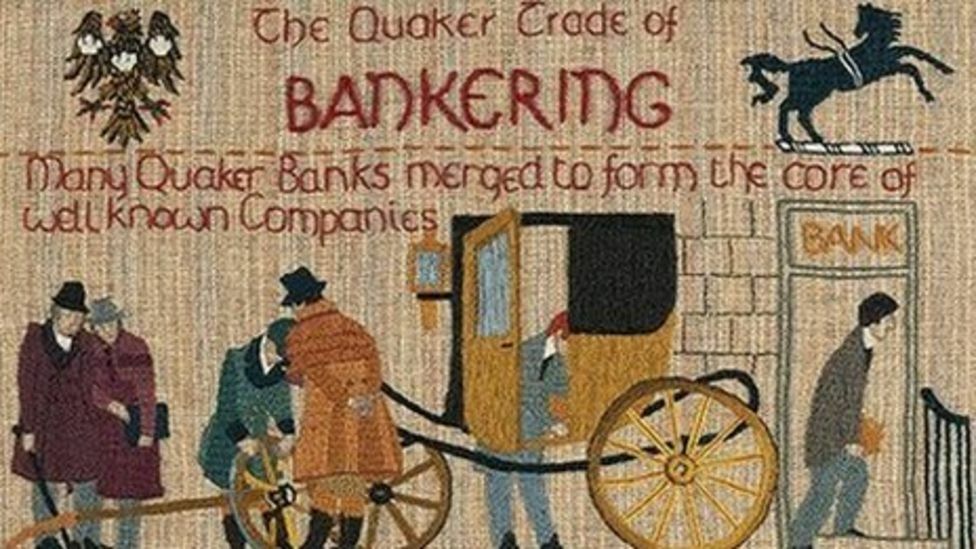

Navigating Quaker history became less than simple because the Society’s very survival offers such a rich seam to be mined, and over the centuries many diverse interests have adapted the Quaker story to champion their values and beliefs. Building from the very earliest histories, our common version of how the sect prospered originates in a late-Victorian morality tale: that of the persecuted Quakers winning through by insisting on telling the truth and diligently refraining from putting sand in their sugar. The idea of the ‘outsider’ is echoed in other elements of the popular story: Quakers were ‘forced’ into Trade as a result of their high-minded refusal to take oaths which barred entry to both universities and ‘The Professions’. Fortunately, this tale also ends well, with commercial Friends somehow rewarded for their sufferings with prosperity. Max Weber, the ‘Father of Sociology’, took a less karmic view, insisting that Quaker beliefs made it essential to be richly endowed with worldly success in order to prove the superiority of their religion. Karl Marx even suggested that Friends’ success resulted from a form of communism in which goods and services were held in common.

Had Weber or Marx been well-versed in the history of the Society, or familiar with the practices promoted in its earliest recorded meetings they would have realised that such claims cannot be sustained. So if neither of these explain the story of Quakerism’s success - what does?

One starting point might be to explain the myth of the ‘Oath’; Quakers were against swearing because it inevitably involved both a lawyer and his fee! Quakers themselves had no use for the legal system, for the Discipline insisted on a process of internal arbitration and appeals to resolve Friends’ disputes. In 1696 the problem largely resolved itself with The Quaker Act which allowed affirmation in most situations where Quaker interests were involved. Yet even before this date, many Quakers would appear to have found ways around this hurdle – since they were over-represented in both the Livery companies of London and in the third ‘profession’ emerging at this time – medicine.

University education was only for a tiny elite: the choice was Oxford or Cambridge, and the goal was preferment in the Anglican church. Numbers of ‘professionals’ was measured in hundreds – except for the Army, and Quakers had removed themselves from that option!

The vast majority of people in the country worked as labourers, or low level artisans. Those who engaged in a trade were the fortunate few – requiring as it did some level of education and the money to buy an apprenticeship – the cheapest of which cost the best part of an average year’s earnings (not unlike a university education today).

Quakers were disproportionately successful because they saw that participation in a trade was not just the best way for individuals to survive, but to ensure the prosperity that would enable the Society to thrive. To this end they developed a policy of effective community support: when the Monthly and Quarterly meetings enquired ‘how does truth prosper among you?’, the question also concerned support for the needs of each fledgling Quaker. Practical assistance ranged from free coal and assistance with rents to providing clothing and even coffins! Practical education was promoted in specially set-up Quaker schools; while each Meeting noted which Friends were in need of apprentices and reviewed the youths in need of occupation. In 1660 Fox specified that legacies to Friends should be set aside to pay the necessary apprentice fee, while collections be used to set Friends up in business. This not only ensured that none were idle in the Lord’s vineyard, but was an investment in people intended to reduce the burden of poor relief.

Once the apprenticeship was completed, the newly qualified tradesman might expect to find a place in their master’s business, while the Quarterly Meetings would look to help the more experienced to take on the business of those Quakers seeking partners or retiring, or even to identify opportunities to open businesses in new towns. While Monthly Meetings would frequently make loans available to Friends needing finance, of far greater importance was the access to credit. Quakers would supply their goods to other Quakers without immediate payment: this enabled new enterprises to stock up, and establish themselves before selling these goods and it was not uncommon for repayments to take several years.

The shared financial support which allowed these investments in education, apprenticeships and businesses led to a very high level of interdependence within the Society. This began in the Meeting House, but extended across the Monthly and Quarterly meetings as Quakers took advantage of first a regional, then a national and for some an international network. The network was unique not just in extent, but in that it was potentially accessible to all who agreed to abide by the Quaker rules – which became known as the Discipline.

Importantly, many early Advices promoted behaviour which supported commercial success. These include using Arbitration and Appeals to avoid law, avoiding smuggled goods, gaming, and luxury, while encouraging every form of thrift - from refusing payment to register births to eschewing mourning costume and gravestones! Quaker Advices encouraged state tax avoidance - spirituous liquors, land ownership, carriages and – while Friends disputed Ecclesiastical law especially tithes – and kept their own registers of births, marriages and deaths to avoid the fees. Such Advices set the Quakers apart from their neighbours, but also kept expenses to a minimum. Above all, Advices stressed Friends must not risk their business in pursuit of worldly success: so interconnected were Quakers that one bankruptcy could bring down many. While both risk and debt were accepted aspect of trade, these were only acceptable if any loss could be sustained.

Administration of Discipline was set down plainly, with local rulings by panels of Friends and appeals to Quarterly and Yearly Meetings, allowing Discipline to act as a regulatory mechanism by which Quaker values were maintained -and good practice in commerce encouraged. Thus were Friends equipped to become successful, trustworthy tradespeople, in a world full of uncertainty and doubt.

What we might learn from this today is another story.

Dr. Andy Fincham is an Associate Tutor at Woodbrooke who researches the relationship between Quaker history and business ethics.

This Q&B academic research project was sponsored by Quakers and Business group

We will discern a response at spring gathering on May 20, 2023.