Grundtvig’s Legacy Offers a Blueprint for Modern Social Justice

Historical examples of successful social transformation become increasingly valuable in our era of growing inequality

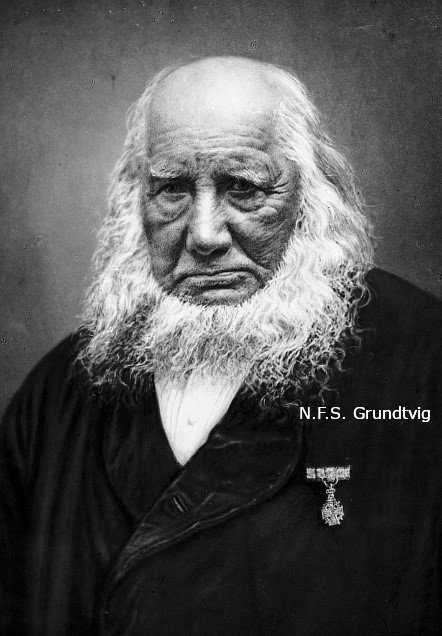

In an era of growing inequality and social division, historical examples of successful social transformation become increasingly valuable. Robert K. Greenleaf’s influential work, The Power of Servant Leadership, presents one such compelling case study through the story of Nikolai Frederik Severin Grundtvig, widely recognised as the “father of Danish Folk High Schools.” Grundtvig’s revolutionary approach to education and social empowerment offers profound insights for contemporary Quakers, business leaders, and social justice advocates seeking practical solutions to address modern inequality.

Denmark’s newly enfranchised peasantry faced enormous challenges after emerging from centuries of serfdom

To understand the significance of Grundtvig’s achievements, we must first appreciate the social landscape of 19th-century Denmark. The country was undergoing a period of dramatic change, with Denmark’s newly enfranchised peasantry emerging from centuries of serfdom. These former serfs had recently acquired small landholdings, representing a monumental shift in the nation’s social structure. However, ownership alone was insufficient to guarantee success or prosperity.

The challenge facing these new landowners was multifaceted. They possessed little formal education, lacked the practical skills necessary for effective land management, and had no experience in the complex world of agricultural commerce. Traditional educational institutions were either inaccessible to them or irrelevant to their immediate needs. It was within this context of opportunity and uncertainty that Grundtvig conceived his revolutionary educational philosophy.

Grundtvig’s servant leadership philosophy equipped individuals with essential skills for success

Despite facing considerable scepticism from established educational authorities and social elites, Grundtvig remained committed to his vision of democratic education. In 1844, he established the first folk high school in Rødding, Southern Denmark, marking the beginning of an educational revolution that would transform Danish society.

These folk high schools represented a radical departure from traditional educational models. Rather than focussing on abstract academic subjects divorced from daily life, Grundtvig’s institutions implemented practical education designed to equip individuals with essential skills for success as new landowners. The curriculum encompassed agricultural techniques, basic literacy and numeracy, civic education, and crucially, the development of critical thinking skills that would enable students to adapt to changing circumstances.

The schools operated on principles of mutual respect and democratic participation, reflecting Grundtvig’s belief that education should empower individuals rather than merely transmit knowledge. Students were encouraged to engage actively in their learning, sharing experiences and insights that enriched the educational experience for all participants.

The cooperative model provided practical benefits that individual farmers could never have achieved alone

Education alone, however, was not sufficient to ensure the success of Denmark’s new peasant landowners. Recognising this limitation, the farmers adopted the cooperative model from England, creating a powerful synergy between individual empowerment and collective action. This combination of education and collaborative business practices proved transformative.

The cooperative movement provided practical benefits that individual farmers could never have achieved alone. By pooling resources, sharing knowledge, and collectively negotiating with suppliers and buyers, these formerly marginalised individuals gained significant economic leverage. They established cooperative dairies, grain elevators, and purchasing associations that reduced costs and improved market access.

More importantly, the cooperative model fostered a sense of community and mutual responsibility that strengthened social bonds and created networks of support. This collaborative approach enabled the entire group to develop successful livelihoods and transition into the middle class, demonstrating the power of collective action in addressing systemic inequality.

The Danish case demonstrates the transformative potential of investing in practical education and collaborative economic models

Reflecting on Grundtvig’s impact, as outlined by Greenleaf, prompts serious consideration of how contemporary Quakers and business leaders can respond to increasing inequality, particularly evident in countries like the United Kingdom. The Danish case demonstrates the transformative potential of investing in practical education and fostering collaborative economic models that prioritise community benefit alongside individual success.

The parallels between 19th-century Denmark and modern society are striking. Today’s gig economy workers, recent immigrants, and those displaced by technological change face similar challenges to Grundtvig’s peasants: they possess potential but lack the specific skills, networks, and resources necessary to thrive in a rapidly changing economic landscape.

Quakers and businesses could implement similar strategies guided by values of equality and social justice

Could not Quakers and businesses, guided by values of equality and social justice, implement similar strategies to empower individuals and enhance societal equity? The answer suggests itself through various contemporary applications of Grundtvig’s principles.

Modern equivalents might include community-based vocational training programmes, worker cooperatives, community land trusts, and social enterprises that combine practical education with collaborative economic structures. Technology offers new possibilities for scaling these approaches, enabling online learning communities and digital platforms that facilitate cooperation across geographical boundaries.

Business leaders committed to social responsibility could establish corporate social responsibility programmes that go beyond charitable giving to create sustainable pathways for economic advancement. This might involve partnering with educational institutions to develop relevant skills training, supporting the formation of worker cooperatives, or investing in community-owned enterprises.

Despite facing considerable scepticism from established educational authorities and social elites, Grundtvig remained committed to his vision of democratic education. In 1844, he established the first folk high school in Rødding, Southern Denmark, marking the beginning of an educational revolution that would transform Danish society.

These folk high schools represented a radical departure from traditional educational models. Rather than focussing on abstract academic subjects divorced from daily life, Grundtvig’s institutions implemented practical education designed to equip individuals with essential skills for success as new landowners. The curriculum encompassed agricultural techniques, basic literacy and numeracy, civic education, and crucially, the development of critical thinking skills that would enable students to adapt to changing circumstances.

The schools operated on principles of mutual respect and democratic participation, reflecting Grundtvig’s belief that education should empower individuals rather than merely transmit knowledge. Students were encouraged to engage actively in their learning, sharing experiences and insights that enriched the educational experience for all participants.

The cooperative model provided practical benefits that individual farmers could never have achieved alone

Education alone, however, was not sufficient to ensure the success of Denmark’s new peasant landowners. Recognising this limitation, the farmers adopted the cooperative model from England, creating a powerful synergy between individual empowerment and collective action. This combination of education and collaborative business practices proved transformative.

The cooperative movement provided practical benefits that individual farmers could never have achieved alone. By pooling resources, sharing knowledge, and collectively negotiating with suppliers and buyers, these formerly marginalised individuals gained significant economic leverage. They established cooperative dairies, grain elevators, and purchasing associations that reduced costs and improved market access.

More importantly, the cooperative model fostered a sense of community and mutual responsibility that strengthened social bonds and created networks of support. This collaborative approach enabled the entire group to develop successful livelihoods and transition into the middle class, demonstrating the power of collective action in addressing systemic inequality.

The Danish case demonstrates the transformative potential of investing in practical education and collaborative economic models

Reflecting on Grundtvig’s impact, as outlined by Greenleaf, prompts serious consideration of how contemporary Quakers and business leaders can respond to increasing inequality, particularly evident in countries like the United Kingdom. The Danish case demonstrates the transformative potential of investing in practical education and fostering collaborative economic models that prioritise community benefit alongside individual success.

The parallels between 19th-century Denmark and modern society are striking. Today’s gig economy workers, recent immigrants, and those displaced by technological change face similar challenges to Grundtvig’s peasants: they possess potential but lack the specific skills, networks, and resources necessary to thrive in a rapidly changing economic landscape.

Applying servant leadership principles could help Quakers and businesses implement similar strategies today

Could not Quakers and businesses, guided by values of equality and social justice, implement similar strategies to empower individuals and enhance societal equity? The answer suggests itself through various contemporary applications of Grundtvig’s principles.

Modern equivalents might include community-based vocational training programmes, worker cooperatives, community land trusts, and social enterprises that combine practical education with collaborative economic structures. Technology offers new possibilities for scaling these approaches, enabling online learning communities and digital platforms that facilitate cooperation across geographical boundaries.

Business leaders committed to social responsibility could establish corporate social responsibility programmes that go beyond charitable giving to create sustainable pathways for economic advancement. This might involve partnering with educational institutions to develop relevant skills training, supporting the formation of worker cooperatives, or investing in community-owned enterprises.

Grundtvig’s model provides both inspiration and practical guidance for creating a more equitable society

Grundtvig’s legacy, as detailed by Greenleaf, serves as a potent reminder of education’s transformative power and the profound impact of collective action on social and economic mobility. His approach offers a practical blueprint for addressing contemporary inequality: combine relevant, empowering education with collaborative economic structures that enable individuals to succeed together rather than compete against one another.

The Danish experience demonstrates that meaningful social change is possible when visionary leaders commit to principles of servant leadership, practical education, and cooperative action. In our current era of growing inequality and social tension, Grundtvig’s model provides both inspiration and practical guidance for those committed to creating a more equitable and just society.

Further reading

Robert K. Greenleaf, the father of the modern servant leadership movement, made a powerful point about a leader’s role on page 137 of his book, “The Power of Servant Leadership.”

Learn more about the origins of this unique educational model by exploring the history of Danish folk high schools.

Related posts:

Servant Leadership: a Quakers enduring vision of for the world of business